Classes are a way of grouping related bits of information together into a single unit (also known as an object), along with functions that can be called to manipulate that object (also known as methods). For example, if you want to track information about a person, you might want to record their name, address, and phone number, and be able to manipulate all of these as a single unit.

Python has a slightly idiosyncratic way of handling classes, so even if you’re familiar with object-oriented languages like C++ or Java, it’s still worth digging into Python classes since there are a few things that are different.

Before we start, it’s important to understand the difference between a class and an object. A class is simply a description of what things should look like, what variables will be grouped together, and what functions can be called to manipulate those variables. Using this description, Python can then create many instances of the class (or objects), which can then be manipulated independently. Think of a class as a cookie-cutter – it’s not a cookie itself, but it’s a description of what a cookie looks like, and can be used to create many individual cookies, each of which can be eaten separately. Yum!

- Python Programming – Classes and Objects

- Introduction to Python Classes (Part 2 of 2)

- How to Check for Object Type in Python | Python type() and isinstance() Function with Examples

- APOLLOHOSP Pivot Point Calculator

Defining a Python Class

Let’s start off by defining a simple class:

class Foo:

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

def printVal(self):

print(self.val)

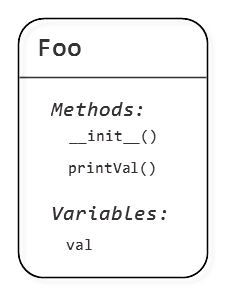

The class is called Foo and as usual, we use indentation to tell Python where the class definition starts and ends. In this example, the class definition consists of two function definitions (or methods), one called __init__ and the other printVal. There is also one member variable, not explicitly defined, but we’ll explain below how it gets created.

The diagram shows what the class definition looks like – 2 methods and 1 member variable. Using this definition, we can then create many instances of the class.

You can see that both methods take a parameter called self. It doesn’t have to be called self but this is the Python convention and while you could call it this or me or something else, you will annoy other Python programmers who might look at your code in the future if you call it anything other than self. Because we can create many instances of a class, when a class method is called, it needs to know which instance it is working with, and that’s what Python will pass in via the self parameter.

__init__ is a special method that is called whenever Python creates a new instance of the class (i.e. uses the cookie cutter to create a new cookie). In our example, it accepts one parameter (other than the mandatory self), called val, and takes a copy of it in a member variable, also called val. Unlike other languages, where variables must be defined before they are used, Python creates variables on the fly, when they are first assigned, and class member variables are no different. To differentiate between the val variable that was passed in as a parameter and the val class member variable, we prefix the latter with self. So, in the following statement:

self.val = val

self.val refers to the val member variable belonging to the class instance the method is being called for, while val refers to the parameter that was passed into the method.

This is all a bit confusing, so let’s take a look at an example:

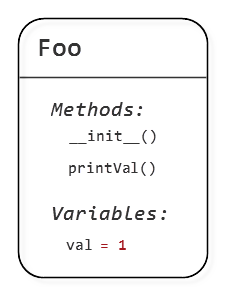

obj1 = Foo(1)

This creates an instance of our class (i.e. creates a new cookie using the cookie cutter). Python automatically calls the __init__ method for us, passing in the value we specified (1). So, we get one of these:

Let’s create another one:

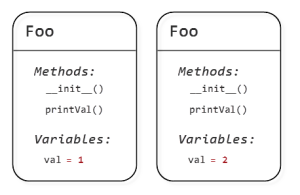

obj2 = Foo(2)

Exactly the same thing happens, except that 2 gets passed in to the __init__ method.

We now have two independent objects, with different values for the val member variable:

If we call printVal for the first object, it will print out the value of its member variable:

>>> obj1.printVal() 1

And if we call printVal for the second object, it will print out the value of its member variable:

>>> obj2.printVal() 2

Standard Python Class Methods

Python classes have many standard methods, such as __init__ which we saw above, that gets called when a new instance of the class is created. These are some of the more commonly-used ones:

__del__: Called when an instance is about to be destroyed, which lets you do any clean-up e.g. closing file handles or database connections__repr__and__str__: Both return a string representation of the object, but__repr__should return a Python expression that can be used to re-create the object. The more commonly used one is__str__, which can return anything.__cmp__: Called to compare the object with another object. Note that this is only used with Python 2.x. In Python 3.x, only rich comparison methods are used. Such as__lt__.__lt__,__le__,__eq__,__ne__,__gt__and__ge__: Called to compare the object with another object. These will be called if defined, otherwise Python will fall-back to using__cmp__.__hash__: Called to calculate a hash for the object, which is used for placing objects in data structures such as sets and dictionaries.__call__: Lets an object be “called” e.g. so that you can write things like this:obj(arg1,arg2,...).

Python also lets you define methods that let an object act like an array (so you can write things like this: obj[2] = "foo"), or like a numeric type (so you write things like this: print(obj1 + 3*obj2).

Python Class Example

Here’s a simple example of a class in action that models a single card in a deck of playing cards.

Python 3.x

class Card:

# Define the suits

DIAMONDS = 1

CLUBS = 2

HEARTS = 3

SPADES = 4

SUITS = {

CLUBS: 'Clubs',

HEARTS: 'Hearts',

DIAMONDS: 'Diamonds',

SPADES: 'Spades'

}

# Define the names of special cards

VALUES = {

1: 'Ace',

11: 'Jack',

12: 'Queen',

13: 'King'

}

def __init__(self, suit, value):

# Save the suit and card value

self.suit = suit

self.value = value

def __lt__(self, other):

# Compare the card with another card

# (return true if we are smaller, false if

# we are larger, 0 if we are the same)

if self.suit < other.suit:

return True

elif self.suit > other.suit:

return False

if self.value < other.value:

return True

elif self.value > other.value:

return False

return 0

def __str__(self):

# Return a string description of ourself

if self.value in self.VALUES:

buf = self.VALUES[self.value]

else:

buf = str(self.value)

buf = buf + ' of ' + self.SUITS[self.suit]

return buf

Python 2.x

class Card:

# Define the suits

DIAMONDS = 1

CLUBS = 2

HEARTS = 3

SPADES = 4

SUITS = {

CLUBS: 'Clubs',

HEARTS: 'Hearts',

DIAMONDS: 'Diamonds',

SPADES: 'Spades'

}

# Define the names of special cards

VALUES = {

1: 'Ace',

11: 'Jack',

12: 'Queen',

13: 'King'

}

def __init__(self, suit, value):

# Save the suit and card value

self.suit = suit

self.value = value

def __cmp__(self, other):

# Compare the card with another card

# (return <0 if we are smaller, >0 if

# we are large, 0 if we are the same)

if self.suit < other.suit:

return -1

elif self.suit > other.suit:

return 1

elif self.value < other.value:

return -1

elif self.value > other.value:

return 1

else:

return 0

def __str__(self):

# Return a string description of ourself

if self.value in self.VALUES:

buf = self.VALUES[self.value]

else:

buf = str(self.value)

buf = buf + ' of ' + self.SUITS[self.suit]

return buf

We start off by defining some class constants to represent each suit, and a lookup table that makes it easy to convert them to the name of each suit. We also define a lookup table for the names of special cards (Ace, Jack, Queen and King).

The constructor, or __init__ method, accepts two parameters, the suit and value, and stores them in member variables.

The special __cmp__ method is called whenever Python wants to compare a Card object with something else. The convention is that this method should return a negative value if the object is less-than the other object, a positive value if it is greater, or zero if they are the same. Note that the other object passed in to be compared against can be of any type but for simplicity, we assume it’s also a Card object.

The special __str__ method is called whenever Python wants to print out a Card object, and so we return a human-readable representation of the card.

Here is the class in action:

>>> card1 = Card(Card.SPADES, 2) >>> print(card1) 2 of Spades >>> card2 = Card(Card.CLUBS, 12) >>> print(card2) Queen of Clubs >>> print(card1 > card2) True

Note that if we hadn’t defined a custom __str__ method, Python would have come up with its own representation of the object, something like this:

<__main__.Card instance at 0x017CD9B8>

So, you can see why it’s a good idea to always provide your own __str__ method. 🙂

Private Python Class Methods and Member Variables

In Python, methods and member variables are always public i.e. anyone can access them. This is not very good for encapsulation (the idea that class methods should be the only place where member variables can be changed, to ensure that everything remains correct and consistent), so Python has the convention that a class method or variable that starts with an underscore should be considered private. However, this is only a convention, so if you really want to start mucking around inside a class, you can, but if things break, you only have yourself to blame!

Class methods and variable names that start with two underscores are considered to be private to that class i.e. a derived class can define a similarly-named method or variable and it won’t interfere with any other definitions. Again, this is simply a convention, so if you’re determined to poke around in another class’s private parts, you can, but this gives you some protection against conflicting names.

We can take advantage of the “everything is public” aspect of Python classes to create a simple data structure that groups several variables together (similar to C++ POD’s, or Java POJO’s):

class Person

# An empty class definition

pass

>>> someone = Person() >>> someone.name = 'John Doe' >>> someone.address = '1 High Street' >>> someone.phone = '555-1234'

We create an empty class definition, then take advantage of the fact that Python will automatically create member variables when they are first assigned.

Also Read: Java Program to Print Heart Star Pattern